Coming Home: Randy Edsall’s Second Act In Storrs

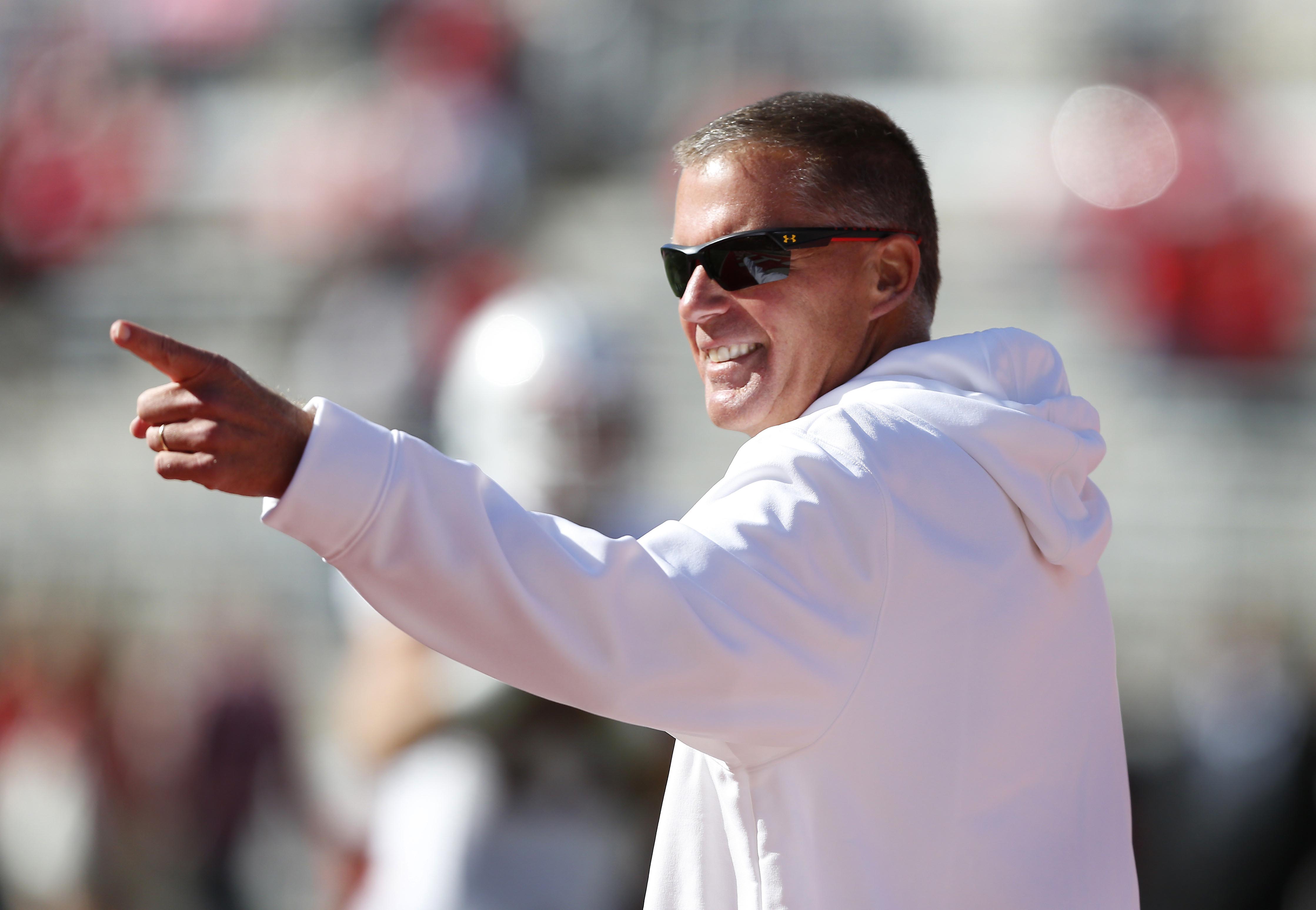

Randy Edsall is back at Connecticut, out to mend fences and recapture the success he had in Storrs before taking the Maryland job.

Randy Edsall is back at Connecticut, out to mend fences and recapture the success he had in Storrs before taking the Maryland job.

You can always go home. Of course, that doesn’t necessarily guarantee the locals will treat your return warmly.

The day after Christmas, Connecticut sacked underachieving Bob Diaco, promptly replacing him with Randy Edsall. As expected, a small slice of the community reacted as if its collective stocking had been stuffed with coal. However, the bulk of the fan base and alumni network got exactly what it wanted for the holidays—a coach who’s already proven he can thrive at one of the most difficult jobs in the FBS.

Edsall is an enigma these days, largely the result of his own transgressions. On the one hand, he’s the architect of Husky football in the modern era and the winningest coach in program history. On the other, his indelicate, abrupt departure to Maryland six years ago left deep wounds.

Edsall turned dust into gold in Storrs over the course of 12 years. In College Park, he failed for four-and-a-half seasons.

This begs the question: which coach did UConn hire? As coaches serving non-consecutive tenures go, will he be Pitt’s Johnny Majors? Or can he become the Northeast’s version of Kansas State legend Bill Snyder?

Understanding the essence of Edsall requires a history lesson.

The Architect

When Edsall arrived at UConn in 1999, fresh off a successful season as Georgia Tech’s defensive coordinator, the Huskies were tucked deep in the football wilderness from a national perspective. They were still playing in the I-AA Atlantic 10 Conference, perennially facing the likes of Delaware, Rhode Island and New Hampshire. Their home, 16,200-seat Memorial Stadium, was a decrepit building better suited for a practice facility or a high school power.

Through a murky haze of obstacles, former athletic director Lew Perkins had an audacious vision of turning Connecticut, of all places, into a viable I-A football entity. And Edsall was the young coach he entrusted with bringing that plan from concept stage to fruition.

In Edsall’s debut, he literally worked out of trailers, diligently trying to elevate marginal talent, spark interest in an indifferent community and plant roots in one of the nation’s most barren recruiting territories. If that wasn’t challenging enough, he was being asked to buck the odds on a campus far better known for producing stars in basketball, soccer, baseball, hockey and even field hockey.

Edsall’s tenure in Storrs began with a 56-17 loss to now-defunct Hofstra, and there were just 7,286 fans in attendance for the team’s final home game that year, another blowout loss. But Edsall was undeterred by the predictably rough start and steep climb ahead, the necessary hallmark of a program builder. He was a decidedly old school, roll-up-the-sleeves coach, with the work ethic and eye for talent to transform this fixer-upper one brick at a time.

Recalibrating Expectations

Why go back to Edsall? Because after six straight losing seasons, three under Diaco and three under Paul Pasqualoni, Connecticut felt the ship needed to be righted by the one man uniquely qualified at exceeding expectations in the Nutmeg State. The one man with the gravitas and secret sauce for winning at a school with zero natural advantages in football. Staples during the Edsall years, such as menacing offensive lines, have absolutely haunted the Huskies and their quarterbacks throughout the current decade.

“You know, I still haven’t met a kid who’s had something bad to say about Randy,” offers Steve Cruz, whose son Jordan Todman was the unanimous Big East Offensive Player of the Year in 2010. “Jordan has always liked Randy, and the two have remained in touch. He’s just such a great coach, and as a parent I liked the fact that he always remained on top of the kids academically.”

Edsall has already overseen the golden years of Husky football, an improbable 12-year period marked by a spate of seminal moments. He guided UConn out of I-AA and ultimately into the Big East, a league it co-championed twice. Under Edsall and his staff, Connecticut appeared in its first-ever bowl game, the 2004 Motor City Bowl. After needing four years to adapt to life at the highest level of college football, the Huskies won at least eight games in six of Edsall’s final eight seasons, including a signature double-overtime win over Notre Dame in 2009. Sold-out, record-sized crowds at the school’s new home, Rentschler Field, witnessed many of the program’s brightest achievements.

“Sure, it was an uphill battle and a tough place to win because of geography,” admits Rob Ambrose, the current Towson head coach and Edsall assistant for seven seasons. “But we had the right people on hand. And we had a vision and a plan, and we worked that plan every single day. We knew we had to grind harder than everyone else, and because we did we wound being ahead of schedule at reaching our goals.”

Creating A Culture Of Success

Even at its peak, Connecticut wasn’t attracting can’t-miss recruits. In all likelihood, it never will. Blue-chippers wind up in Storrs to play on hardwood not grass. So, Edsall & Co. understood a different approach was necessary, namely curating their ideal, undeveloped kids who were willing to hustle in anonymity and then coaching them up. And for a time, few schools were doing a better job of developing unpolished gems than UConn. Basically, if a student-athlete wasn’t willing to bring it, both on the field and in the classroom, the Huskies weren’t a good fit.

“With Coach Edsall’s staff, you always know where you stand,” says Dan Ryan, a four-time letter-winning offensive tackle. “Our winning culture was built off the field first, through tough discipline. It went from the classroom to the practice field, and from the practice field to game day. Coach Edsall insisted we were physical, did the little things well and were always mentally tough.”

By 2007, the UConn brand had been successfully forged in its coach’s image—an assertive downhill ground game, a perennially salty defense and a penchant for methodically converting overlooked high school recruits into pro-caliber performers. In 2009, a remarkable four Huskies, RB Donald Brown, CB Darius Butler, OT Will Beatty and LB Cody Brown, were selected in the first 63 picks of the NFL Draft. Later that fall, nine former Huskies were on NFL rosters. Nine, at a school one decade earlier that was operating as a middling I-AA outfit, sans adequate facilities, personnel or momentum.

“Coach didn’t just have an eye for talent,” offers Scott Lutrus, the former two-time captain and All-Big East linebacker. “He had an eye for kids willing to put in the work to reach their potential. He fostered a competitive environment in everything we did, but we were also bound together like family. The staff instilled such a tight-knit culture, a team-first environment in which we played for each other and looked out for each other at all times. That camaraderie that Coach helped create is something I still enjoy today with my Husky teammates, and plan to for the rest of my life.”

The program’s pinnacle occurred late in 2010. The Huskies, struggling at midseason, caught a second-half tailwind that would forever change the program’s identity. They won the final five games of the regular season, three by a field goal or less, to earn the Big East’s automatic berth to a BCS bowl game. So long, second-tier postseason events played in front of docile, half-empty crowds. Hello, big time and a date with powerhouse Oklahoma in the storied Fiesta Bowl. UConn had officially arrived, forcing the college football universe to take notice of the evolution engineered by Edsall.

Unfortunately for UConn football, it’s been a straight shot downhill ever since Glendale. The climb to the Fiesta Bowl was incremental and painstaking. The descent was rapid and unforeseen. The Sooners outclassed the Huskies, 48-20, on an unseasonably chilly evening in the desert. However, Connecticut lost far more than a game at University of Phoenix Stadium. The Huskies lost their leader and their innocence in one fell swoop, a bittersweet turn of events that has yet to be fully reconciled.

As the deflated Huskies flew home, their coach was on a different flight to Baltimore to replace Ralph Friedgen as Maryland’s head coach. There’s absolutely no shame in accepting a new job, particularly when the compensation and the stage are greater. Edsall spent 12 years pinning Connecticut football on the map, so he’d paid his dues and then some. But when he failed to notify his players, the ones who’d helped make this promotion possible, of his exit, he committed a cardinal coaching sin that’s left unhealed scars in pockets of the Husky community to this day.

Second Act

Edsall is back in Storrs. Considerably grayer around the temples, and presumably wiser, than when his opening act began almost two decades ago, the 58-year-old is no longer the new kid pushing a boulder up the mountain. In fact, he’s the elder statesman of an American Athletic Conference littered with 30 and 40-somethings hoping to use the league as a launching pad to a Power Five promotion. Fortunately, that metaphorical boulder is considerably more cobble-sized since he did most of the heavy lifting in his first go-round with the Huskies.

Edsall is once again tasked with elevating the Connecticut program. However, the specificity of those tasks is distinctly different in Act II. The foundation is already set. The transition to a higher level of competition ended long ago. Tradition? Far more established than it was two decades ago. This time around, Edsall’s early focus centers on rebuilding bridges to the past, mending fences and proving as quickly as possible that his stopover in Maryland was an aberration. Fans in Connecticut will passionately support their team, but they can also be unapologetically fair-weathered and tetchy when results aren’t delivered.

“A lot of people in the region are willing to give Randy a second chance,” says Jim Fuller, the Husky football beat writer for the New Haven Register. “And I immediately heard a lot of fans saying they planned to renew their season tickets. The previous administration (Diaco’s) never fully comprehended just how difficult it is to win here. As long as Randy gets back to winning, fans will have a short memory about what took place in the past.”

Edsall’s first month back at UConn has been a mixed bag, though to assign any interim grades at this stage would be foolhardy. He’s started strongly with his staff, landing young up-and-comers Rhett Lashlee and Billy Crocker to coordinate his offense and defense, respectively. Luring Lashlee from Auburn was especially meaningful, because it signaled the notoriously conservative Edsall is willing to open up his attack and allow more latitude and flexibility to his assistants.

However, January also marked the pulling of a scholarship from Raritan (N.J.) High School LB Ryan Dickens, an otherwise anonymous recruit whose story mushroomed into a national clarion call for what is unseemly with college sports. Dickens was offered by the old Husky regime, left at the altar by the new one and forced to scramble at the eleventh hour of the recruiting cycle. Like it or not, that’s the kind of thing that routinely happens when staffs turn over. Still, the optics for Edsall, as he looks to buff his image, are just plain awful. And he cannot afford to be persona non grata in a nearby, talent-laden state like New Jersey.

Earlier this century, Connecticut provided a road map of what’s possible for future division-climbers, like Appalachian State or Western Kentucky or Old Dominion. Sure, the FBS can be a scary and demanding place to compete, but the Huskies proved it can be conquered when the leadership and the personnel share similar visions for tomorrow.

“We had to work real hard to find the right kid, the kid who was willing to be a part of something that’s not built yet,” says Ambrose, with growing reflection in his voice. “If you didn’t want to work, you wouldn’t survive with us. We were going to be blunt and honest, because if the kids didn’t trust us it never would have worked. We didn’t cut corners. There were no bags of money. We did things the right way. We built something.”

Edsall, minus some goodwill, is no longer being asked to build, so much as rebuild – both the program and his own reputation. In turning back the clock by welcoming Edsall home, UConn hopes he can rekindle the spark that existed during his triumphant first stop in Storrs.

MORE: Tom Izzo’s Rant Was About His Players, Not Michigan State Fans